The troubled fate of the French Crown jewels during the 1848 revolution Archived Message

Posted by Arthur  on January 14, 2017, 1:28 pm, in reply to "Queen Marie Amelie and the French Crown Jewels" on January 14, 2017, 1:28 pm, in reply to "Queen Marie Amelie and the French Crown Jewels"

As mentioned by Lorenzo in one of his posts above, the history of the French Crown jewels during the troubled days of the revolution of February 1848, which caused the sudden collapse of Louis-Philippe's regime, is worth a novel full of suspense and drama. Bernard Morel's Les Joyaux de la Couronne de France (pages 331-333) gives a thrilling account of these days (the additional information in italic and between brackets are by myself):

"On 24th of February, 1848, around noon, the government was more and more unable to resist the riots. Troops stationed near the Tuileries [the royal palace] and the Palais-Royal [the Parisian palace of the Orleans family] gathered within the Carrousel courtyard [the Tuileries Palace's main courtyard, facing the Louvre], whose gates were closed. M. de Verbois [the treasurer of the Civil List service, whose offices and personal apartment were in a wing perpendicularly adjacent to the Tuileries Palace; the Crown jewels were stored in a strongbox hidden inside a brick wall of the Civil List service's offices], left without instructions, took the initiative, helped by his wife and by a maid, to take the assets in banknotes and coins deposited by the Royal family and kept by the Civil List service, and to bring them to one of his friend's home, who lived in the nearby Rue des Pyramides. Then, while unsuccessfully looking for General Jacqueminot [general officer commanding the National Guard] to ask him for a platoon of guards to protect the treasure of the Civil List, Verbois saw the rioters entering the Carrousel courtyard, forcing the troops backwards. Verbois went back to his friend's home Rue des Pyramides. The mob then entered the apartments and the underground floors of the Palace.

Around 2.00 PM, a groop of rioters began shooting to the door of the underground cellar situated just below the treasure's cashier desks, which were not kept by soldiers. A workman of the Civil List service, named Nô, came downstairs to the cellar, told the rioters he would help them, and opened the door. The overexcited men demanded only wine, and Nô showed them the place where Verbois' wine bottles were stored. But as there were only few bottles, Nô feared they might threaten to go upstairs where the treasure was kept. Nô claimed that a platoon of soldiers was upstairs and convinced the rioters to withdraw and led them instead to the cellars of General Jacqueminot. There, in the kitchen, they ate a lunch which had been prepared for the General, and rushed onto his 10,000 bottles of wine! All this resulted in a violent orgy, and the day after, twelve lifeless bodies were found on the wine-soaked floor...

Meanwhile, taking advantage from this distraction, Nô managed to reach the Tuileries in order to look for a platoon of guards. He came back with Sergeant Bex and six grenadiers, whom he helped to enter into the Treasure's offices, where they formed a small protection platoon with a few employees and workmen of the service. Yet, around 7.00 PM, because of the general confusion, some people succeeded to enter the office in which were kept the registers recording the gifts, subsidies and gratifications granted by Louis-Philippe. A lot of files were possibly embarrassing for several members of the former opposition, now at the head of the new revolutionary regime... The files were torn off or lacerated, and burnt. This resulted in the beginning of a blaze, prompting the soldiers and firemen to arrive; the soldiers exchanged a few gunshots with the occupants and ousted them from the offices.

While the orgy in the cellars was still going on, a clerk went to Schefer, central cashier, to prevent him of what was happening in the Treasure's offices. Schefer was sick, but gave a key to his son, who came and opened one of the boxes of the Civil List, witnessed by several attendants. He withdrew 331,000 Francs in banknotes and 34,000 Francs in coins. Someone took two purses of coins into his bag, committing the other people present to do the same, in order to transport the money safely to the Banque de France; but he was never seen again... The rest of the money, including the 331,000 Francs in banknotes shoved by a grenadier into his bearskin cap, arrived safely to the Banque de France. But the Crown jewels were still in the Treasure's offices, hidden in the wall, as well as the jewels of the Princess of Joinville [one of Louis-Philippe's daughters-in-law] and various assets worth 3 to 4 million Francs.

Verbois, from his friend's home Rue des Pyramides, had seen the blaze in the subsidies office of the Civil List service. He then came back to the office with his son-in-law, Harenbourg, and Baron Fain. They held a quick meeting in presence of Sergeant Bex, and decided to bring the Princess of Joinville's jewels and the assets to the Finance ministry on the next day [the Finance ministry was located, at the time of these events, between Rue du Mont-Thabor and Rue de Rivoli, on the North side of the Tuileries gardens, so not very far from the Palace]. This was done in the morning of the 25th February, with the jewels and assets placed onto a barrow, covered with thick blankets. But the Crown jewels still remained in their strongbox hidden in the wall, because it was necessary to bring the three keys together to remove it...

Still on the 25th February, Verbois, holder of one of the three keys, went and met at 4.00 PM chief-of-staff Guinard and the Inspector General. They decided to summon for the next day at 10.00 AM the other two holders of the keys in order to open the Crown jewels strongbox, in the presence of Goudchaux, the Finance minister.

On 26th February, at 10.00 AM, the holders of the three keys, Verbois, Maréchal and Crown jeweller Constant Bapst, were there at the time scheduled, but the Finance minister had still not arrived at noon. At the same time, General Courtais [commanding officer of the National Guard, newly appointed by the republican revolutionary authorities], popped up and declared that, considering the situation, the jewels had to be transported immediately to the headquarters of the National Guard. The strongbox containing the jewels was then taken from the wall in which it had been kept hidden for more than 15 years, and opened. General Courtais put into his jacket the records and inventories which were in the strongbox, while the jewel caskets were taken from the strongbox and laid onto the table, or even onto the ground. This careless handling of the jewels raised sharp protests from Constant Bapst, who demanded a strict responsibility for everyone and a descriptive record of the jewels taken from the strongbox. But General Courtais refused. Bapst bitterly declared that such careless handling made the stealing of jewels very easy and possible, and that he would rather have thrown his key into the Seine river if he had known that things would go this way. But General Courtais took absolutely no regard of the former Crown jeweller’s critics and ordered the persons and a few national guards present in the room to take the many jewel boxes and to follow him. Courtais himself gave the example, taking in his hands the box containing the crown of Charles X. Some of the smallest boxes were shoved into the pockets, prompting renewed vain yells from Constant Bapst: "Nothing in the pockets!". But everything went so quickly and in such a confusion that any serious supervising turned out impossible. About twelve persons carried the various jewel boxes: General Courtais, Carson and Lacour (employees of the Civil List’s Treasury), Laurin and Barvin (cashdesk clerks), Pessar (office clerk), Nô (workman), Allary (postal clerk) and a few national guards. Verbois and Bapst both refused to carry any box.

Following General Courtais, still holding the royal crown, the small group went to the office of chief-of-staff Guinard through a dark underground corridor, stumbling at each step because of the empty bottles with which the floor of the corridor was covered. Courtais ordered the people carrying the jewel boxes to lay them down in a corner of Guinard’s office; the boxes were covered with a blanket and remained them until 4.00 PM under the supervision of the employees of the Civil List and several national guards. A finance inspector, de Codrosy, then arrived and had immediately a document drawn up, recording the number of jewel boxes present in the room; he then had the boxes put into five bags, which were sealed and loaded into a carriage usually used for house moves. An escort led by Colonel Degousée accompanied the carriage, which arrived at 5.00 PM to the Finance ministry. The five bags were delivered to de Colmont, Secretary General of the ministry, Thomas, central cashier, and Levasseur, General Comptroller, who affixed new seals onto the bags.

On 9th March, 1848, the republican provisory government issued a new decree, after which, "considering that the Diamonds of the Crown belonged to the Nation, and that the circulation of currency was insufficient", the Finance minister was allowed to sell the jewels at prices which were to be determined by experts.

On 12th March, the new Finance minister Garnier-Pagès had a thorough verification of the Crown jewels realized, witnessed by several persons, including Constant Bapst and Verbois. It was then noted that what Bapst had feared had happened: one of the boxes was missing! This box contained a hat button in diamonds (whose main stone was the "2nd Mazarin", a 25.37 carat diamond of an exceptional beauty, which was part of the 18 diamonds bequeathed in 1661 by Cardinal Mazarin to King Louis XIV, surrounded by 20 brilliant diamonds totalizing 4 carats) and two diamond pendeloques of two rose-diamonds each (the two largest roses weighted 13.49 and 12.07 carats). These jewels represented a value, according to the last inventory made in 1832, of 293,112.50 Francs. During the verification, Garnier-Pagès, dazzled by the diamond-encrusted royal crown made for Charles X, noticed the "Regent" diamond mounted at the top of the crown, and asked Bapst about its value. "Twelve millions", Bapst replied. "Well, the minister replied, we will sell it to the Tsar of Russia!"

The following day, Constant Bapst, who assured he had seen the box containing the missing jewels on the table when the strongbox had been opened, and Verbois checked back the underground corridor through which the transport of the jewels had been processed. After all, the box, which was of rather small dimensions, could have slipped from a pocket while everyone was stumbling. Unfortunately, they found nothing. The jewels had really been stolen! And the stealing had certainly happened during the transport of the jewels, as the jewels had been under constant supervision the rest of the time. The police investigated, but without result. Constant Bapst wrote to all the main gem-cutters and gem-retailers of Europe to urge them to retain any suspicious stone, but to no avail, except a reply from a London jeweller. The former Crown jeweller hence travelled to London, but unfortunately the jewel noticed by the jeweller was not the right one. None of the missing stones was ever found again.

Finance minister Garnier-Pagès’ remark almost became a reality. As mentioned earlier, a decree dated 9th March, 1848, had opened the way to the sale of the Crown jewels. On 2nd June, 1848, a commission composed of Guillemarden, finance general inspector, Thomas, finance general treasurer, and former Crown jeweller Constant Bapst, checked all the parures, comparing them with the inventory made in 1832. Fortunately, the decree of 9th March, 1848, had no further consequence. Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon Ist, was soon elected member of Parliament, and eventually President of the Republic on 10th December, 1848. He already had the secret intention to restore the imperial regime, and he consequently blocked the sale of a jewel collection of which he intended to have sooner or later a good use..."

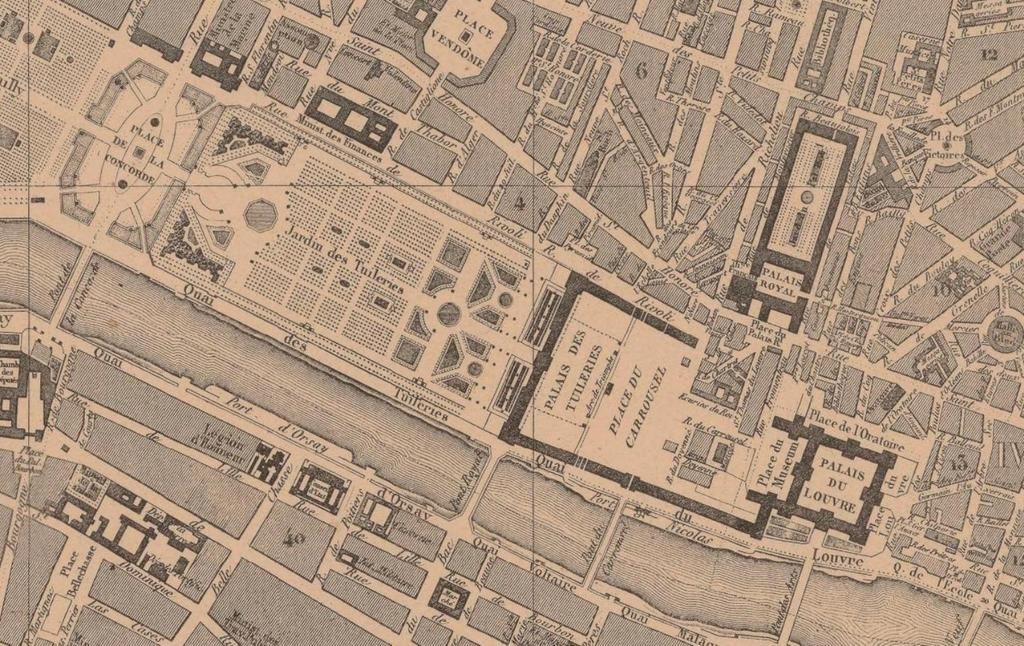

To help you locate the various places mentioned above, here is a cropped version of a plan of Paris made in 1842, centrered on the Tuileries Palace ("Palais des Tuileries"). The Civil List service was in the wing perpendicular at the north extremity of the Tuileries Palace, along the Rue de Rivoli (both the Palace itself and this adjacent wing are drawn darker). The Rue des Pyramides is the short street right in the axis of the Tuileries palace at the north, between the Rue de Rivoli and the Rue St Honoré. The Finance ministry is in the upper left corner of the picture ("Minist. des Finances") and is drawn in a darker shade too.

|

|